Secrets of The Appalachian Trail

The Appalachian Trail is iconic. You’ve probably heard of it—the 2,190+ mile long hiking trail nicknamed the “AT” that stretches all the way from Georgia to Maine? And if you’ve ever lived anywhere near the East Coast of the U.S., chances are you either know someone or know someone who knows someone who hiked the entire trail.[1] This massive undertaking, known as “thru-hiking” is a pop culture trend —there are hundreds of books detailing people’s experiences thru-hiking the AT, the most famous being Grandma Gatewood’s Walk (the inspiring story of the first woman who thru-hiked the AT alone at age 67 and who used her celebrity to save the trail from extinction),[2] Hollywood movies about thru-hikes that went wrong — both comedically (A Walk in the Woods) and horrifically (Beacon Point)[3], and at least one college offering students credit for accomplishing thru-hikes![4] And then there are those folks who love a challenge and make it their life’s goal to break an AT thru-hiking record, such as the fastest time to complete the trail (Karel Sabbe: 41 days, 7 hours, and 39 minutes), most hikes completed (Warren Doyle: 9 thru-hikes and 9 section hikes) and oldest person to thru-hike the AT (M.J. “Nimblewill Nomad” Eberhart: 83 years old).[5]

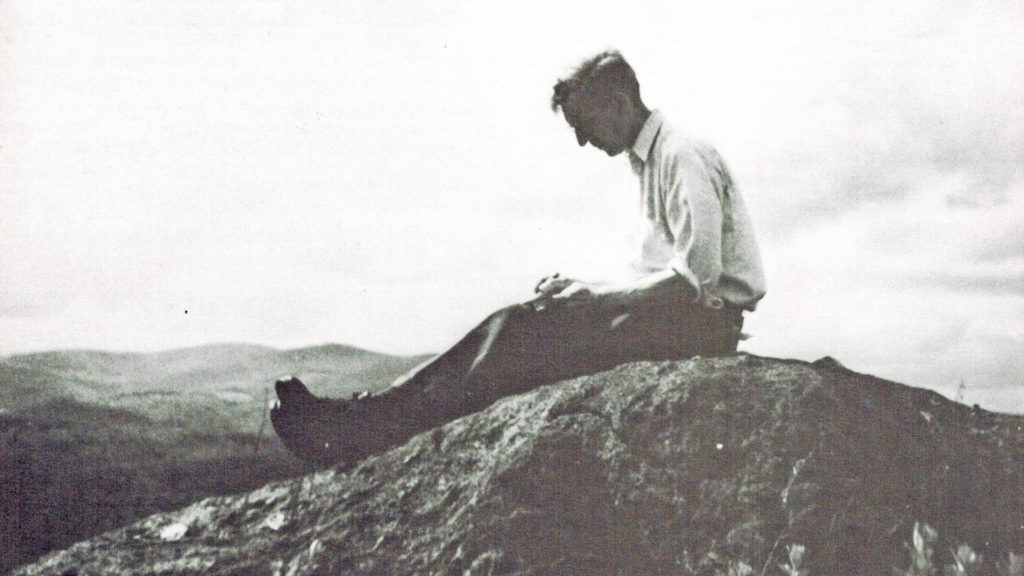

But the Appalachian Trail isn’t just about thru-hiking. In fact, Benton MacKaye, the man who first proposed the concept of the AT wasn’t thinking about thru-hiking at all. He was grieving the loss of his wife, Jessie Hardy “Betty” Stubbs MacKaye, who suffered bouts of severe anxiety and committed suicide by drowning herself in the East River at the age of 45. In 1921, MacKaye, a forester, conservationist, and community planner, devastated by his wife’s tragic death, left their home in New York City to stay at his friend Harris Whitaker’s farm in western New Jersey that was “high in the mountains…and not a soul in sight.”[6] Here, MacKaye turned to the task of finding solutions to what he called “the problem of living”— the increased stresses upon the population caused by rapid urbanization and growing economic disparities between the cities and rural areas in the aftermath of WWI. MacKaye envisioned a footpath along the ridges of the Appalachian mountains accessible to the residents of metropolitan areas along the Eastern seaboard that would not just promote economic well-being for small towns in the foothills, but also provide a form of wilderness therapy for city dwellers battling mental health issues.[7]

In October 1921, long before science confirmed the detrimentaleffects of stress upon mental health, in his groundbreaking essay proposing “An Appalachian Trail” that was edited by Whitaker and published in The Journal of the American Institute of Architects, MacKaye wrote: ”Most sanitariums now established are perfectly useless to those afflicted with mental disease—the most terrible, usually, of any disease. Many of these sufferers could be cured. But not merely by ‘treatment.’ They need acres not medicine. Thousands of acres of this mountain land should be devoted to them with whole communities planned and equipped for their cure.”[8]

Benton MacKaye’s words cut right to the core when you know howpersonally affected he was by his wife’s suicide—a tragic consequence of untreated mental illness. It’s highly likely that Benton was thinking about Betty when he conceived of a multi-state hiking trail because long-distance walking and hiking were among Betty’s favorite pastimes, along with championing progressive causes. A few years before she married Benton, Betty organized and led a walk from New York City to the state capital of Albany—a distance of 148 miles—to advocate for a woman’s suffrage bill! This feat attracted considerable media attention and undoubtedly attracted the attention of MacKaye too as it’s no secret that the MacKaye’s marriage was a partnership of political activism as well as mutual affection.[9]

But why has the origin story of the Appalachian Trail remained asecret when the AT is the most famous footpath in the world attracting 3million visitors each year? I’ve been hiking the AT for decades now, as a“day-hiker,”[10] (someone who hikes the trail all day and goes back to a warm bed at night, or maybe a local brew pub first, a hot tub second, and a warm bed third). I’ve hiked in about half of thestates the AT runs through—VT, NY, PA, MD, VA, WV, and TN. So why did I just learn the story of the MacKayes this year? On my birthday, I decided to visit the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (“ATC”) headquarters, located at the “psychological midpoint” of the AT in Harpers Ferry, WV.[11] I was pleased to meet Dave, concierge of all things AT-related, who bears a striking resemblance to Santa Claus (except skinnier). When I asked Dave about the distinction between the ATC and the Appalachian Mountain Club (“AMC”)[12]of which I’m a member, Dave gave me a detailed explanation of the AT’s origins and directed me to an exhibit containing photographs of Benton MacKaye and excerpts from his illuminating essay, including his idea to utilize the AT’s “acres” as a “cure” for mental illness. I was so touched by MacKaye’s words that tears sprang to my eyes. But I knew I had just scratched the surface; I wanted to learn everything I could about the fascinating couple underlying the myth of the Appalachian Trail.

The more I read about the lives of Benton & Betty MacKaye, the more realized why their story might have gotten left out of the AT legend. The MacKayes were socialists who lived during the “First Red Scare” of 1919-1920, which was a time when Americans feared a communist or anarchist revolution in America much like the Bolshevik revolution that had just occurred in Russia in 1917.[13] Although the folks in the MacKayes’ social circle may not have demonized them for their socialist political affiliation, people outside of that circle thought their ideas and tactics were too radical. For example, when the MacKayes were living in Wisconsin, Benton lost his job at The Milwaukee Leader in the wake of Betty’s controversial proposal for a “bride strike,” where women would withhold sex from their husbands to force them to stop engaging in violence and wars. Brilliant idea but not well received at the time. Sadly, it was after the MacKayes relocated to New York City that Betty’s mental state began rapidly deteriorating. Further evidence suggests that Benton’s theoretical differences with other Appalachian Trail Conference leaders underpinned the reason why he was not chosen to be part of the Executive Committee, despite the fact he delivered the keynote speech at the conference and drafted the constitution.[14]

In the following decades, MacKaye became increasingly disillusioned with the progress of the Appalachian Trail project because he envisioned the AT as a wilderness trail that would serve as a catalyst for social transformation, not necessarily a continuous trail that would serve as a recreational resource as envisioned by other leaders who represented the interests of the hiking community. While the AT may not be the pristine wilderness that MacKaye imagined (for example, Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park that MacKaye fought against unsuccessfully is traversed by 1.2 million visitors each year!), that doesn’t mean MacKaye’s transformative vision has gone unfulfilled.

I have always thought of the Appalachian Trail as a haven—a place of refuge where you can escape noise, pollution, work and family stresses, the toxic political climate, you name it. When you’re out on the AT, everything else disappears. There’s only the white-blazed trail, and the serenity and challenge it offers. The AT is notoriously rocky, so you’ve got to wear boots with good ankle support. To prevent injury, every step you take needs to be a mindful one. You’ll want to choose the pace that works for you—fast enough to maintain your momentum so that you can get to your destination and back before nightfall—but not so fast that you can’t stop to take in the beautiful scenery, eat a snack, take a few pix, and chat with other hikers. There’s an instant feeling of community out on the trail because you know hundreds of feet have trodden where yours have just landed. But you don’t think about how old those hikers were or how in-shape they were or what race they were or what gender they were. You’re immune from the “cancer of comparison” because none of those speculatory statistics will help you achieve your goal, so that self-defeating cycle of negative thoughts (known as rumination) will drift out of your mind if it ever entered in the first place. All that’s left is a sublime sense of peace.[15]

For me, what’s most valuable about hiking the AT is that it gives everyone the chance to engage in a single-minded physical activity surrounded by nature and free from distraction, a rare opportunity in today’s world of frantic multi-tasking in the face of an endless stream of competing demands. Some people call it a Zen-like spiritual practice, some call it "getting in the zone," but no matter what you call it, science supports Benton MacKaye’s hypothesis that walking in nature provides measurable mental health benefits, including the reduction of anxiety and depression.[16] Some of this has to do with endorphins, the “feel-good” hormones our body produces when we exercise, but it’s our reconnection with nature that’s the key to the mental clarity and freedom from rumination that distinguishes hiking from working out at the gym.[17] If he were alive today, I believe Benton MacKaye would be pleased to know there’s a non-profit all-volunteer organization called HIKE for Mental Health that’s dedicated to organizing hikes to promote the mental health benefits of hiking and raising funds for mental health research and trail conservation.[18]

During the COVID pandemic, when wewere all coping with unprecedented stressors without our usual social outlets, I started hiking portions of the Appalachian Trail in Shenandoah National Park between Thanksgiving and Christmas, and by now, it’s become a tradition. The looming approach of these two holidays arriving in rapid succession at the end of the year never fails to fill me with a sense of dread, and I’m not the only one. “Holiday Dread” is a very real thing. Google it and hundreds of articles will pop up. According to a 2019 survey, 61% of Americans dreaded the holidays; a 2021 survey put the number at 48%.[19] An obvious cause is the fear of overspending in light of the exaggerated focus on obligatory gift-giving, which has intensified due to inflation. But there are also the emotional pangs from missing loved ones who have died or family members estranged by feuds or divorce. And what about just feeling worn-out and exhausted at the end of a long year, like a runner at the end of a marathon, craving rest and relaxation rather than overeating and incessant conversation? But I think it’s the unrealistic expectation of a month-long state of cheerfulness that’s the worst part of all, like when people tell you to smile and you just want to punch them in the face.

This year, on the weekend after Thanksgiving, I hiked the 7.1 miles of the AT from the Pinnacles Picnic Area to Mary’s Rock and back. Although it had been a year ago when I last completed this hike, it felt as if I had just hiked it yesterday. When I reached the summit, which is a special place to me that I envision in my prayers, I was thrilled to find it looked exactly as I had pictured it in my mind! On the way back down, I was suddenly struck by the idea to write this piece about the MacKayes, the origins of the AT, and the mental health benefits of hiking (there’s that cool mental clarity thing again). With Christmas just around the corner, it hasn’t been easy to carve out the time to get these thoughts out of my head and into the computer. But I felt it was absolutely necessary that I did write this now, if only to convince you that it’s precisely at times like these, where you feel the agonizing constraints of time and money and social pressure tightening like a Victorian lady’s corset that you really need to get out in the fresh air and take a hike! Not to diminish your importance here, but the world won’t fall apart if you take a day off from your daily routine. Ask a friend or neighbor to walk your dog. Leave some money for your kids to order takeout. Tell your boss you’re taking time off to fulfill some personal obligations. Give yourself the gift of hiking this Christmas because you’re worth it! Your body, mind, and soul will be eternally grateful.

[1]This probability is an example of the “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” principle.See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_Degrees_of_Kevin_Bacon#:~:text=Six%20Degrees%20of%20Kevin%20Bacon%20or%20Bacon's%20Law%20is%20a,ultimately%20leads%20to%20prolific%20American

[2] Veryfew people knew about the AT before Emma Gatewood appeared on TV and SportsIllustrated to shed light on the unsafe stretches of trail and issue a call toaction to maintain and preserve the trail for posterity. For more about“Grandma Gatewood” and her biography written by Ben Montgomery, see https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/18527222

[3]This article reviewing the best AT movies (including documentaries where youget a sense of reality) is featured on a blog written by thru-hikers forthru-hikers that also contains a lot of good resources and practical tips foranyone interested in hiking the AT. https://appalachiantrail.com/20140806/10-best-appalachian-trail-movies/

[4]For more info, please see this article about the Emory & Henry College“Semester-A-Trail” program at https://www.backpacker.com/news-and-events/news/emory-and-henry-college-credit-hiking-appalachian-trail/

[5] “NimblewillNomad” is Eberhart’s trail name. Thru-hikers are like an unofficial club thathas established its own trail culture, jargon, and etiquette. A well-known featureof trail culture is the use of “trail names,” which are nicknames thru-hikersuse to refer to each other on the trail. You’re not supposed to make up yourown trail name, your “trail family” are supposed to give it to you, and dependingon how sick and twisted they are, it can be based on something very stupid or embarrassingyou’ve done that will literally follow you wherever you go. For some of worst trail names ever, see https://www.reddit.com/r/AppalachianTrail/comments/wg90do/worst_trail_names_2022_edition/

[6] FromHarris Whitaker’s letter to Benton MacKaye in 1921, excerpted from TheTragic Origins of the Appalachian Trail (thedailybeast.com)

[7]For more about the life and career of Benton MacKaye, see AppalachianTrail Histories | Benton MacKaye · Builders (appalachiantrailhistory.org)

[8] Ifyou’re a hiker or a nature lover, I strongly encourage you to read MacKaye’sentire proposal. It’s beautifully written from the heart, but also incredibly visionaryand forward-thinking even by today’s standards. AnAppalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning | Appalachian TrailConservancy

[9]For more about the life and work of Betty MacKaye, see Biographical Sketchof Jessie Belle Hardy Stubbs MacKaye | Alexander Street Documents

[10] Fora great beginner’s guide to day hiking the AT, see https://appalachiantrail.org/explore/hike-the-a-t/day-hiking/

[11] Establishedin 1925, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (“ATC”) is the leading organization tasked by Congressto oversee the maintenance, management, and conservation of the AT andsurrounding lands. https://appalachiantrail.org/explore/faqs/.The precise geographical midpoint of the AT is inaccessible to the generalpublic, so Harpers Ferry is considered the psychological midpoint because it’s closeto the midpoint and accessible to the general public because it’s adjacent to aNational Park.

[12]The Appalachian Mountain Club (“AMC”) is comprised of many local chaptersstretching from the Northeast through the Mid-Atlantic that provide volunteeropportunities for education, conservation, and recreation along the AT. The AMCchapters up in New Hampshire and Maine are particularly robust, offering lovelyvisitor accommodations in lodges and cabins, as well as a variety of courses fromwilderness first aid to landscape and wildlife painting. Home | Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC)(outdoors.org)

[13]For more about the First Red Scare, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Red_ScareAppalachian

[14]See “Success and Failure” in this wonderful article published on the ATCwebsite. AppalachianTrail Histories | Benton MacKaye · Builders (appalachiantrailhistory.org)

[15]By extolling the mental health benefits of hiking, I am by no means suggestingthat going out for a day hike will eradicate all forms of mental illness andsuicidal tendencies, only that there is scientific evidence indicating that it mayimprove symptoms and possibly prevent suicide. Certainly, if you or someone youknow has been having thoughts of suicide or is severely depressed, contact theAmerican Foundation for Suicide Prevention at https://afsp.org/

[16] Agreat example is this 2105 Stanford study https://news.stanford.edu/2015/06/30/hiking-mental-health-063015/

[17] Thiswarm-hearted blog post written by a thru-hiker discusses 4 ways that hikingimproves your mental health https://thetrek.co/4-ways-hiking-improves-your-mental-health/and it contains a link to a scientific study showing that increasing ourexposure to nature reduces rumination and promotes mental well-being. https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.1510459112

[18]For more information about HIKE for Mental Health, or to donate or volunteer,see https://www.hikeformentalhealth.org/

[19]See https://www.fox5dc.com/news/61-percent-of-americans-dread-the-holidays-because-of-spending-survey-suggests and https://www.lendingtree.com/credit-cards/study/holiday-shopping-sentiments-survey/