Jiri Trnka

Imagine a world instilled with curiosity, excitement, and wonder composed for adult sensibilities. It would likely be a world created from the childlike traits of play, persistence, humor, creativity, goodness combined with the adult knowledge and experience of deception, disappointment, power, and suffering. This is the world that Jiri Trnka created in his many poignantly fascinating stop motion animated films.

Imagine a world instilled with curiosity, excitement, and wonder composed for adult sensibilities. It would likely be a world created from the childlike traits of play, persistence, humor, creativity, goodness combined with the adult knowledge and experience of deception, disappointment, power, and suffering. This is the world that Jiri Trnka created in his many poignantly fascinating stop motion animated films.

Jiri Trnka is not a widely known name in our current era dotted with talentless hyper-famous reality TV stars and soulless CGI movies, but his influences are undoubtedly felt and far reaching. Trnka’s creative work inspired several generations of artists and filmmakers such as Kihachiro Kawamoto, Stephen and Timothy Quay, Bretislav Pojar, Zdena Deitchova, Jan Svankmajer, and Stephen Bosustow, the co-founder of United Productions of America. Trnka was also incredibly innovative; countless children and their families throughout Europe and North America have enjoyed his films and books. But even more important, Trnka’s legacy is directly tied to the intrinsic value of artistic expression and the human need to resist totalitarian control over the creative spirit.

Trnka was a Czechoslovakian born artist and he lived and worked under authoritarian communist rule. Although he was not a political artist, he did create work with an artfully hidden political message of resistance. Through his creative adaptation of puppetry, story, and technique, Trnka became enormously famous within Czechoslovakia while walking his secretly defiant tightrope. Due to his fame, the Communist Party sought to appropriate his popularity by subsidizing his films and awarding him the dubious honor of “National Artist.” After his death in 1969, Trnka’s veiled message of resistance and liberty was discovered and his films were banned until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1993. It is believed that Trnka’s influence would have been greater if his films had not been widely outlawed by the Communists after his death.

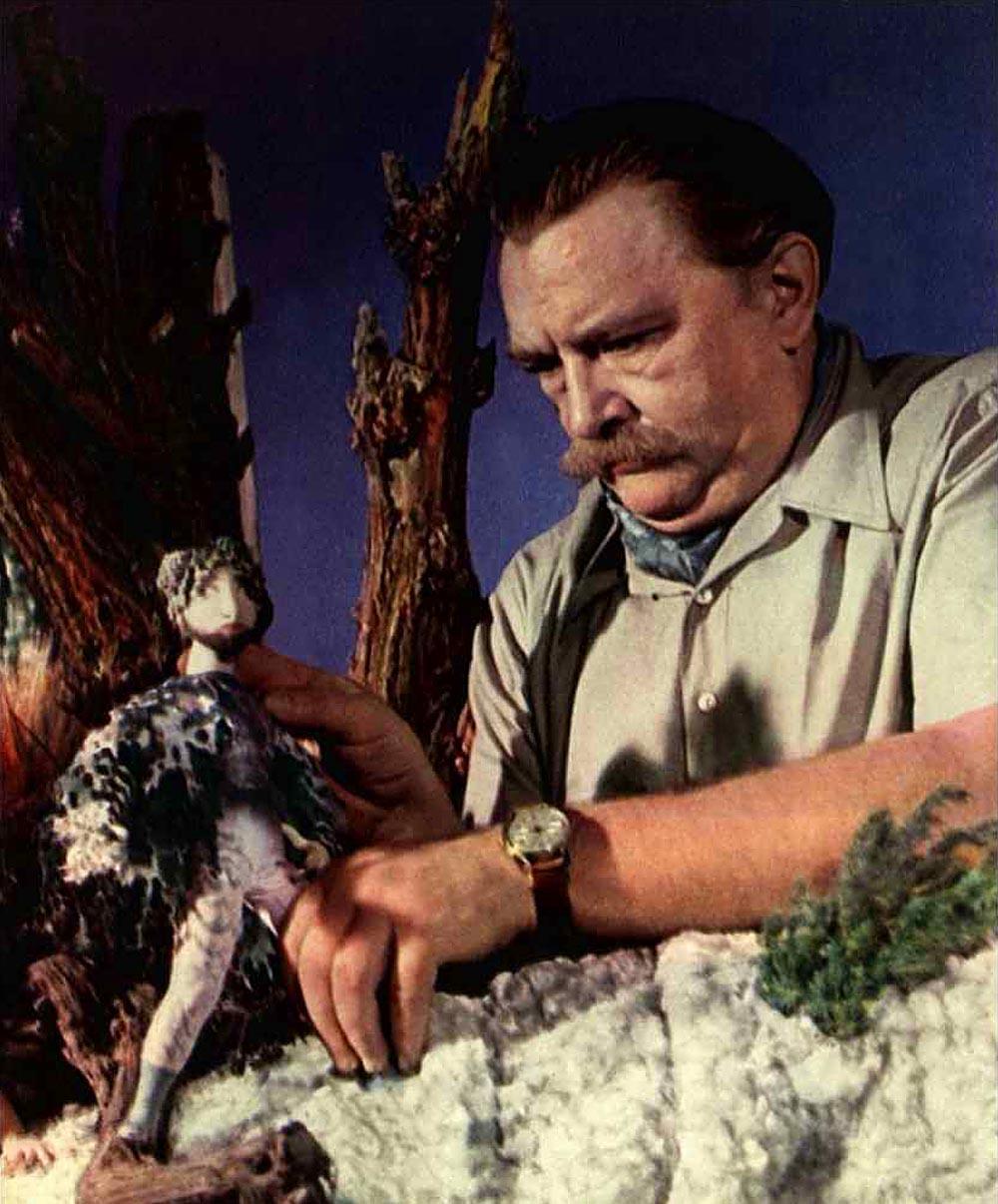

As an artist, Jiri Trnka was extraordinarily creative and his skills and techniques were amazingly diverse. He was a wildly multifaceted prodigious creator, and he easily glided between numerous mediums such as illustration, painting, wood carving, sculpture, animation, set design, puppetry, and stop motion film; however, it can be argued that his greatest area of artistic expression was storytelling.

Trnka’s own creative story began when he was a young boy living in Plzen, Czechoslovakia. His father was a plumber and his mother was a dressmaker. Raised in a poor family of laborers, they struggled for life’s necessities and as a result, young Jiri needed to help the family earn money. His grandmother taught him to carve wooden toys and sew clothes, which inspired a robust passion for puppetry. After performing his first puppet shows for his friends, Trnka got a job when he was only 8 years old at a local theater owned by Josef Skupa, a relatively famous puppeteer. Skupa trained Trnka and later encouraged him to attend the Academy of Art and International Design in Prague.

After completing his education, Trnka worked as an illustrator for a newspaper and pursued becoming a fine art painter. Then in 1936, at 24 years old, he started a puppet theater, which enjoyed a modest level of popularity until it was forced to close due to the outbreak of World War II.

Trnka adapted by working as a stage designer and a free agent illustrator specifically for children’s books. Although best known for his stop motion films, Trnka first earned fame as an illustrator. During his short career, he illustrated over 130 children’s books, including the Brother’s Grimm Fairytales, the Hans Christian Andersen Stories, Fireflies, and The Garden, which Trnka authored as well. Several of Trnka’s books were met with international success and received prestigious awards such as the Hans Christian Andersen Award, the highest honor available to an illustrator of children's books. Trnka’s books were quite common in the U.S. after World War II, and it is ironic that a man who lived and worked under the totalitarian thumb of a brutal Communist government inspired generations of American children during the Cold War.

Trnka illustrated in pencil, watercolor, oils, and inks. According to Trnka’s biographer: “By painting the dreamlike aspects of reality Trnka was doing the same as the surrealist, but his illustrations have none of the cruelty or artistic ruthlessness of surrealism. His roaming brush reflected a child’s roaming mind, with its ability to concentrate, its tendency to fantasy.” This theme of maintaining a connection to childlike thinking and feeling appears throughout Trnka’s work, especially in his animation and stop motion films.

When he was 33 years old, Trnka entered the field of animation with short, two-dimensional hand drawn films. In 1946, he submitted three of these films – The Gift, Animals and Robbers, and The Spring Man and SS – to the first Cannes Film Festival. All three films were selected for viewing and they were each well received. In a surprising turn, Trnka’s Animals and Robbers won the short film category. Trnka also received positive reviews for The Gift, which critics from the Penguin Film Review hailed it for its “pure sense of graphic design” and a French critic described it as “the Citizen Kane of animation.”

Despite the impressive accolades for Trnka’s two-dimensional animated shorts he decided to direct his attention toward puppets and stop motion animation films. Dissatisfied with the industrial, assembly line nature needed to create hand drawn animation, Trnka also believed that the process weakened his originality. As a result, Trnka started his own studio and focused his attention on transfiguring traditional Czech folk stories using three-dimensional puppets and stop motion. The first film that came out of Trnka’s fledgling studio was the ten-minute long Bethlehem. The film was well received and his puppets were described as being full of charisma and gracefully nimble.

After his initial success, Trnka completed five more short films inspired by Czech folk stories and combined and packaged the films as a single feature-length film titled Spalicek (1947). In English-speaking markets the film was titled The Czech Years. Trnka collaborated with renowned composer Vaclav Trojan to write the score, a partnership that continued until Trnka’s death. This film won the Venice Film Festival prize and later, two segments from this film – Jaro (Spring) and Legenda o sv. Prokopu (Legend of St. Prokop) – were banned as religious propaganda by the Communist Party.

Trnka eventually made five feature-length puppet stop motion films, including the Emperor’s Nightingale and A Midsummer Night's Dream, which are often considered his best feature films. Emperor’s Nightingale was an immediate success due to its powerful message and interesting mix of live and stop motion to tell a story of a young boy who was battling both an illness and the feelings of alienation and loneliness. The narrative bounces between real life and the boy’s unconscious dreams, where his toys and other items in his room transform into fanciful characters and objects from a far-off land. Interestingly, the English version of the film was created with commentary provided by Boris Karloff. Interestingly, although the Communist censors detected an underlying theme of impeding liberty, they didn’t ban the film. In all likelihood, this is because the film was made with puppets and the story was included within the regime’s approved literary repertoire.

In contrast to Emperor’s Nightingale, Trnka’s A Midsummer Night's Dream was at first not warmly received. It is not clear why, but it was probably related to Trnka’s innovative use of film techniques and camera positioning. Later the film was recognized as a “stunningly beautiful, highly faithful adaptation of Shakespeare’s play.” The film is often described as “astonishingly beautiful” and “achingly tender” and critics also have commented on the impressive focus on design, which was rare for Czech films of that time period. Trnka shot the film with two different cameras, which means he painstakingly positioned the puppets twice, and as a consequence, two versions of the film exist. In one of these cameras, Trnka used Eastmancolor film, which was of exceptionally high quality and thus, very expensive. Trnka toiled on this film for several years, sacrificing his health to attain his artistic vision; he was immensely committed to his art and valued it deeply.

Trnka’s last and arguably greatest film is The Hand (1969), a short stop motion work about the conflict that occurs when a totalitarian authority interferes with an artist’s freedom to create. The film starts with a happy, innocent artist (a potter) who is content making pots for his beloved flowers. This nameless artist lives an uncomplicated life without the luxuries of television, radio, newspapers, or even books. He lives in a small modest room furnished with only a bed and a manually operated pottery wheel. A single window provides light and a comforting breeze. Despite his humble circumstances, we recognize that the artist has the autonomy to make his own choices.

As the film progresses, we learn that the artist spends his days making pots, which he stacks in the corner of his room, most likely waiting to be filled with his adored plants; we don’t see him filling or selling the pots, just creating them. We also see him dancing through the room, his face glowing with joy and his movements revealing a sense of optimism and delight. He is undoubtedly happy making pots and content with his life.

Soon the artist is visited by a domineering, authoritarian figure in the shape of a white-gloved hand, which tries to convince the artist to create sculpture according to its specifications. The Hand attempts to bribe the artist with modern luxury goods like radio and TV. (Apparently, the Hand’s goal is to melt the artist’s mind so that it could be easily manipulated by propaganda). Steadfast, the artist politely and persistently refuses.

Switching tactics, The Hand changes its color to black and makes hostile aggressive demands to the point of assault in order to break the artist’s will. Then, The Hand uses sex as a means of enslaving the artist’s soul, thereby transforming him into a controllable puppet. Imprisoned in a cage and forced to carve a stone monument of The Hand, the artist’s body is devoid of joy as it is pulled by the marionette strings of fear, force, and power.

Awaking from his trance, the artist briefly escapes his predicament only to end up dying from fear. Once again, The Hand takes control over the artist and his work. By sponsoring a state funeral for the artist that celebrated his association with the authoritarian power, The Hand effectively eviscerated the artist’s message.

Clearly the film is a commentary on Trnka’s life and a striking protest against the control imposed upon him by the communist Czechoslovakian government. Interestingly, when The Hand was first released it did not garner attention from the Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakian government. It was thought of as just another animated film created by a prominent Czechoslovakian filmmaker.

The Hand was Trnka’s last film and it is often described as his masterpiece. Sadly, four years after its release, Trnka died from heart disease. Ironically, he was given a state funeral in much the same fashion as the protagonist of his final film. It wasn’t until after Trnka’s death in 1969 that the government finally recognized The Hand’s message and promptly banned the film, confiscated copies, and made it illegal to own or view the film until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1993.

The Hand is a powerful film that through Trnka’s favored medium of puppetry inspires memories of the childlike traits of play, persistence, humor, creativity, and goodness, while also communicating a deeper, more harrowing adult message of deception, disappointment, power, and suffering. Like Trnka’s life, it resonates with a message of hope and celebrates the power of creativity.

Jiri Trnka has not only gifted us with an astoundingly creative and diverse body of work, but his legacy reminds us to think critically about the relationship between government power and individual expression, to appreciate the intrinsic value of art and creativity, and to dream about a world filled with the childlike qualities of curiosity, excitement, and wonder.