Flanders Fields

On Thanksgiving, the national holiday when Americans are supposed to express gratitude for their prosperity (but what they really do is watch football and gorge themselves on turkey and pumpkin pie) I decided to take a tour of the World War I battlefields in Belgium and to remind myself of how fortunate I am to have been born in the U.S.A. I reserved a seat on the Flanders Fields tour led by Quasimodo Tours, a small business run by a husband (Belgian) and wife (Australian) team that have been earning consistently excellent customer reviews since they began operating in 1990.

Billed as a day-long tour of battlegrounds, cemeteries, monuments, and memorials to the brave young men from the far corners of the globe who fought (and died) along the Ypres Salient during the Great War, I could only imagine the magnitude of our tour guide’s task. How do you deliver the somber facts of war so that they enrich the mind and expand the heart without pushing people down a spiral staircase of depression that would spoil their holiday?

Our tour guide, Philippe, was up to the challenge. He’s as jaded as you would expect a local guy to be whose job it is to talk about the senseless death and destruction of his people at the hand of invading neighbors. But I couldn’t help feeling that there had to be a wellspring of hope for humanity flowing deep within him somewhere, or Phillipe would have chosen to do something else with his life.[1]

We departed Bruges early in the morning on a tour van holding maybe 10 people, and ideal number, which afforded everyone the opportunity to personalize, converse, and ask questions. I was the only American in our group, which was comprised mainly of British chaps, with some Canadians and Aussies mixed in.[2] Our first stop was the German war cemetery of Langemark, which was the scene of the first gas attacks by the German army, marking the beginning of the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915. More than 44,000 soldiers were buried at this site; four life-size bronze statues of “mourning soldiers” watch over them from the cemetery’s border. I didn’t think that anything could have possibly made this scene any sadder until Philippe told us that he rarely, if ever, takes any German visitors here.

Next, we visited the St. Julien Canadian memorial at Vancouver Corner, also known as “The Brooding Soldier,” which was carved from a single piece of granite and stands an imposing 11 meters tall. It commemorates the Canadian 1st Division in action on April 22nd to 24th, 1915, which held its position on the left flank of the British Army after the German Army launched the first ever large-scale gas attack against 2 French divisions to the left of the Canadians. For these 3 days, the Canadians kept fighting in the face of the most horrible method of biological warfare ever invented, and lost 2,000 casualties before reinforcements arrived.

While traversing the ridge of Passchendaele, infamous for thousands of soldiers dying in mud-filled trenches without gaining barely a meter of territory, I reflected on British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s candid admission that it was “one of the greatest disasters of the war . . . No soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign . . ." [3] What I failed to comprehend was why no one had the sense to speak out in protest at the time.

A highlight of the tour in terms of sheer beauty was the Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing, assigned to the UK in perpetuity by King Albert I of Belgium in recognition of the sacrifices made by the British Empire in the defense and liberation of Belgium during the war. The largest cemetery for Commonwealth forces in the world, 11,956 Commonwealth soldiers are buried there along with some German POWs. Artfully designed by Sir Herbert Baker, Tyne Cot is perfectly situated on a rise overlooking the pastoral landscape, making it the most visually stunning soldiers’ resting place I have ever seen, with scarlet rose bushes dotted against the uniform markers carved from white Portland stone.

Our visit to the Hooge Crater Museum on the Ypres-Menin Road was full of surprises. Who would ever think that such a fascinating collection of First World War uniforms, displays, and artifacts as well as an interesting film would find their home in a renovated chapel? [4] For lunch, we had the pleasure of dining on delectable pâté sandwiches at the café adjoining the museum, where my British companions delighted in their red wine and I delighted in my Diet Coke, which isn’t easy to find in Europe.

Next, we walked around the preserved battlefield at Hill 60, where only a few eerie concrete bunkers still remain. The Germans made this steep hill impregnable during the war, so a steadfast division of crazy stubborn Australians decided to build a network of tunnels beneath it, where they planted a bunch of land mines that were eventually detonated under German lines, creating one of the largest explosions in history reportedly heard in London and Dublin.[5]

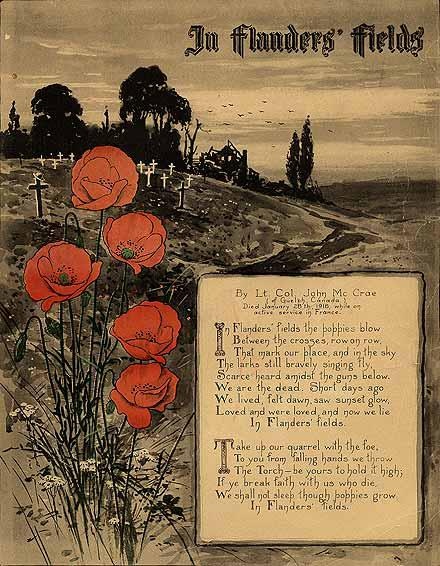

Our next destination was the Medical Station and adjoining cemetery nearby Essex Farm, which is believed to be the location where Major John McCrae wrote his famous poem In Flanders Fields after burying his friend, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, who was killed by a German artillery shell during the 2nd battle of Ypres on May 3rd, 1915.

During our visit to the Yorkshire Trench, which was hidden beneath the shadow of a wind energy/biofuel plant, we learned that this original British trench was discovered in 1992 by a group of amateur archaeologists called “The Diggers," who have devoted countless hours to unearthing and analyzing hundreds of artifacts as well as the remains of 155 soldiers from the UK, France, and Germany, who were lost in battle for 70 years. An arduous and grisly task, no doubt, but hopefully one that brought a feeling of peace to the families of the fallen.

The final stop on our tour was the City of Ypres, which, after having been reduced to rubble during the Great War, was miraculously reconstructed in the Flemish medieval and renaissance styles to resemble the original pre-war city at the behest of King Albert and other far-sighted dignitaries. Unfortunately, our day trip from Bruges did not allow enough time to tour the reputable In Flanders Fields Museum, but Philippe encouraged us to come back and visit it on another occasion.[6] We did have plenty of time, however, to wander around the impressive Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, a gargantuan archway overlooking the river that was built by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) to commemorate soldiers from all the Commonwealth nations (except New Zealand) who died in the Ypres Salient and have no known grave.[7] Incredibly, every night at 8:00 pm since July 2, 1928, buglers from the Ypres fire brigade have conducted a “Last Post” tribute to the warriors who died defending their city.[8]

For me, the most unforgettable moment of the Flanders Fields tour was not a formal battle site, burial ground, or memorial, but a brief pit-stop at a farmer’s field, where a black swan was swimming in a pond in the foreground and a windmill was spinning on the distant flat-line horizon. It looked just like a scene out of a Flemish painting except for the huge artillery casing protruding up out of the soil. Philippe told us there isn’t a day that goes by without a farmer turning up artillery shells or other potentially explosive materials with his tractor. Although most of them have been destroyed by a special Belgian bomb squad, these 100-year-old buried explosives still cause injuries and even death. In May, 2014, two men were killed from an artillery shell or grenade that detonated while they were laying the foundation for a new factory being constructed in Ypres.[9] While the history books say that World War I officially ended with the signing of the Armistice in 1918, if people are still dying as a result of it, did it ever really end? I don’t think so.

A multitude of thoughts popped into my mind as I stood there watching the swan glide gracefully across the pond. My Uncle Donald is a farmer who doesn’t have to worry about getting blown to bits on the off-chance that his John Deere tractor hits a grenade. What’s more, the U.S. has never been invaded or occupied by other nations. We haven’t endured that kind of oppression.[10] We’ve never been refugees huddled together on a raft on the open sea with a 50% chance of survival.[11] Maybe if we had been, we would spend less time complaining about everything that’s wrong with the world and spend more time counting our blessings when we ask for another helping of mashed potatoes at Thanksgiving.

[1] At first, you might think this is total projection on my part until you zoom in for a closer look. Sure, it’s entirely possible that Philippe wasn’t any good at making chocolate or beer or any other Belgian specialty that keep the tourists flocking to Bruges, and that he just so happens to excel at memorizing and recounting historical facts. Because tourism is a huge chunk of the economy in Bruges, Phillipe gives historical tours because he’s good at it and it brings in bucks. This doesn’t require any faith in humanity . . . or does it? Quasimodo Tours will not continue to operate with empty vans. Its success depends entirely upon people caring about other people who died over 100 years ago-and not just care enough to offer a passing thought or prayer-but care enough to sacrifice hours of their holiday that they could have spent eating or drinking or shopping! Now, that takes some firm faith in humanity.

[2] This ratio is what I expected in light of the fact that the Commonwealth nations did the bulk of the fighting for the Allies in this region, suffered massive amounts of casualties, and built the majority of the monuments and memorials.

[3] Lloyd George, David. War Memoirs of David Lloyd George, Vols. I-VI. London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson (1933).

[4] For more detail on exhibits at the Hooge Crater Museum, see http://www.hoogecrater.com/en/museum/

[5] If you’re into spelunking, Australians, or both, check out the film “Beneath Hill 60” that came out about it in 2010, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/beneath_hill_60/

[6] For more information on the In Flanders Fields Museum, see http://www.inflandersfields.be/en

[7] Only UK casualties that occurred before August 16, 1917 are commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing. UK servicemen who died after that date and New Zealand servicemen are named on the Tyne Cot Memorial. Other memorials to fallen New Zealanders can be found at Messines and Polygon Wood.

[8] The only exception to this daily ritual was during the four years of the German occupation of Ypres from May 20th, 1940 to September 6th, 1944.

[9] For more on this sad story, see http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26654314

[10] I’m not saying Americans don’t oppress each other, all the while claiming to be more tolerant than everyone else. We’re internationally recognized experts at that great hypocrisy, and ridiculed for it all over the globe.

[11] In the four years since October 2013, the Mediterranean crossing has claimed the lives of at least 15,000 refugees and migrants, accounting for more than half of the 22,500 refugees and migrants who have died or gone missing globally. See http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/09/iom-refugees-dying-quicker-rate-mediterranean-170917035605080.html